Hey there! In my previous post Booking a Meeting Room with Alexa – Part One, I talk about how to build up the Interaction Model for your Skill using the Alexa Developer Console. Now, I’ll talk about how to write code that can handle the requests.

Setting Up

I chose to use JavaScript to write the skill, as I wanted to try something a little different to Java which is what I normally use. Alexa has an SDK that allows you to develop Skills in a number of languages including Java and Javascript, but also C#, Python, Go and probably many more. I chose Javascript because of its quick load time and conciseness. I’ve written a previous Skill in both Javascript and Java, the former taking < 1 second to execute and the latter taking ~ 2.5 seconds. They both did the same thing, but Java apps can become bloated quickly and unknowingly if you pick certain frameworks, so be weary when choosing your weapon of choice and make sure it’s going to allow you to write quick responding skills. Waiting for Alexa to respond is like waiting for a spinning wheel on a UI, or like your elderly relative to acknowledge they’ve heard you… I’m sure you know what I mean.

To develop in Javascript, I used npm for managing my dependencies, and placed my production code under “src” and test code under “test” (sorry, Java idioms kicking in here!). I used npm init to create my package.json, which includes information about my package (such as name, author, git url etc.) and what dependencies my javascript code has. I later discovered that you can use ask new to create a bootstrapped skill, which you can then use to fill the gaps with your business logic.

Regarding dependencies, there’s a couple of key ones you need for Alexa development: ask-sdk-core and ask-sdk-model. I also used the ssml-builder library, as it provides a nice Builder DSL for crafting your responses.

Skill Structure

Skills have an entrypoint for receiving a request, and then delegate off to a specific handler that’s capable of servicing it. The skeleton of that entry point looks like this:

const Alexa = require('ask-sdk-core');

var Speech = require('ssml-builder');

let skill;

exports.handler = async function (event, context) {

if (!skill) {

skill = Alexa.SkillBuilders.custom()

.addRequestHandlers(

<Your Handlers Here>

)

.addErrorHandlers(ErrorHandler)

.create();

}

const response = await skill.invoke(event, context);

return response;

};So in your top-level handler, you specify one or more RequestHandlers, and one or more ErrorHandlers. Upon calling the create() function you get returned a Skill object, which you can then use to invoke with the received request.

Lazy initialisation of the singleton skill object is because your lambda code can stay active for a period of time after it completes a request, and can handle other requests that may subsequently occur. Initialising this only once speeds up subsequent requests.

Building a RequestHandler

In the middle of the Alexa.SkillBuilders code block, you can see my <Your Handlers Here> placeholder. This is where you pass in RequestHandlers. These allow you to encapsulate the logic for your Skill into manageable chunks. I had a RequestHandler per Intent that my Skill had, but it’s quite flexible. It used something similar to the chain of command pattern, passing your request to each RequestHandler until it finds one that can handle the request. Your RequestHandler has a canHandle function, which returns a boolean stating whether it can handle the request or not:

const HelpIntentHandler = {

canHandle(handlerInput) {

return handlerInput.requestEnvelope.request.type === 'IntentRequest'

&& handlerInput.requestEnvelope.request.intent.name === 'AMAZON.HelpIntent';

},

handle(handlerInput) {

const speechText = 'Ask me a question about Infinity Works!';

return handlerInput.responseBuilder

.speak(speechText)

.reprompt(speechText)

.withSimpleCard('Help', speechText)

.getResponse();

}

};As you can see above, the canHandle function can decide whether or not it can handle the request based on properties in the request. Amazon has a number of built in Intents, such as AMAZON.HelpIntent and AMAZON.CancelIntent that are available to your Skill by default. So it’s best to have RequestHandlers that can do something with these such as providing a list of things that your Skill can do.

Under that, you have your handle function, which takes the request and performs some actions with it. For example that could be adding two numbers spoken by the user, or in my case calling an external API to check availability and book a room. Below is a shortened version of my Room Booker Skill, hopefully to give you a flavour for how this would look:

async handle(handlerInput) {

let accessToken = handlerInput.requestEnvelope.context.System.user.accessToken;

const deviceId = handlerInput.requestEnvelope.context.System.device.deviceId;

let deviceLookupResult = await lookupDeviceToRoom(deviceId);

if (!deviceLookupResult)

return handlerInput.responseBuilder.speak("This device doesn't have an associated room, please link it to a room.").getResponse();

const calendar = google.calendar({version: 'v3', auth: oauth2Client});

const calendarId = deviceLookupResult.CalendarId.S;

let event = await listCurrentOrNextEvent(calendar, calendarId, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate);

if (roomAlreadyBooked(requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate, event)) {

//Look for other rooms availability

const roomsData = await getRooms(ddb);

const availableRooms = await returnAvailableRooms(roomsData, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate, calendar);

return handlerInput.responseBuilder.speak(buildRoomBookedResponse(requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate, event, availableRooms))

.getResponse();

}

//If we've got this far, then there's no existing event that'd conflict. Let's book!

await createNewEvent(calendar, calendarId, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate);

let speechOutput = new Speech()

.say(`Ok, room is booked at`)

.sayAs({

word: moment(requestedStartDate).format("H:mm"),

interpret: "time"

})

.say(`for ${requestedDuration.humanize()}`);

return handlerInput.responseBuilder.speak(speechOutput.ssml(true)).getResponse();

}Javascript Gotchas

I’ll be the first to admit that Javascript is not my forte, and this is certainly not what I’d call production quality! But for anyone like me there’s a couple of key things I’d like to mention. To handle data and time processing I used Moment.js, a really nice library IMO for handling datetimes, but also for outputting them in human-readable format, which is really useful when Alexa is going to say it.

Secondly… callbacks are fun… especially when they don’t trigger! I smashed my head against a wall for a while wondering why when I was using the Google SDK that used callbacks, none of them were getting invoked. Took me longer than I’d like to admit to figure out that the lambda was exiting before my callbacks were being invoked. This is due to Javascript running in an event loop, and callbacks being invoked asynchronously. The main block of my code was invoking the 3rd party APIs, passing a callback to execute later on, but was returning way before they had chance to be invoked. As I was returning the text response within these callbacks, no text was being returned for Alexa to say within the main block, so she didn’t give me any clues as to what was going wrong!

To get around this, I firstly tried using Promises, which would allow me to return a Promise to the Alexa SDK instead of a response. The SDK supports this, and means that you can return a promise that’ll eventually resolve, and can finalise the response processing once it does. After a bit of Googling, I found that it’s fairly straightforward to wrap callbacks in promises using something like:

return new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

dynamoDb.getItem(params, function (err, data) {

if (err) reject(err);

else {

resolve(data.Item);

}

});

});Now that I’d translated the callbacks to promises, it allowed me to return something like the following from the Skill, which the SDK would then resolve eventually:

createNewEvent(calendar, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate).then(result -> return handlerInput.responseBuilder.speak("Room Booked").getResponse();

)Unfortunately, I couldn’t quite get this to work, and it’s been a couple of months now since I did this I can’t remember what the reason was! But things to be wary of for me are the asynchronous nature of Javascript, and Closures – make sure that objects you’re trying to interact with are in the scope of the Promises you write. Secondly, using Promises ended up resulting in a lot of Promise-chains, which made the code difficult to interpret and follow. Eventually, I ended up using the async/await keywords, which were introduced in ES8. These act as a lightweight wrapper around Promises, but allow you to treat the code as if it were synchronous. This was perfect for my use case, because the process for booking a room is fairly synchronous – you need to know what room you’re in first, then check its availability, then book the room if it’s free. It allowed me to write code like this:

let deviceLookupResult = await lookupDeviceToRoom(deviceId, ddb);

let clashingEvent = await listCurrentOrNextEvent(calendar, calendarId, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate);

if (!clashingEvent) {

await createNewEvent(calendar, calendarId, requestedStartDate, requestedEndDate);

let speechOutput = new Speech()

.say(`Ok, room is booked at`)

.sayAs({

word: moment(requestedStartDate).format("H:mm"),

interpret: "time"

})

.say(`for ${requestedDuration.humanize()}`);

return handlerInput.responseBuilder.speak(speechOutput.ssml(true)).getResponse();

}That to me just reads a lot nicer for this particular workflow. Using async/await may not always be appropriate to use, but I’d definitely recommend looking into it.

Speech Synthesis Markup Language (SSML)

The last thing I want to discuss in this post is Speech Synthesis Markup Language (SSML). It’s a syntax defined in XML that allows you to construct phrases that a text-to-speech engine can say. It’s a standard that isn’t just used by Alexa but by many platforms. In the code snippet above, I used a library called ssml-builder which provides a nice DSL for constructing responses. This library then takes your input, and converts it to SSML. The code above actually returns:

<speak>Ok, room is booked at <say-as interpret-as='time'>9:30</say-as> for an hour</speak>Alexa supports the majority of features defined by the SSML standard, but not all of them. I used https://developer.amazon.com/docs/custom-skills/speech-synthesis-markup-language-ssml-reference.html as a reference of what you can get Alexa to do, and it’s still quite a lot! The main thing I had trouble with was getting SSML to output times in a human-readable way – even using the time hints in the say-as attributes resulted in pretty funky ways to say the time! That’s when moment.js came to the rescue, as it was able to output human-readable forms of the times, so I could avoid using SSML to process them entirely.

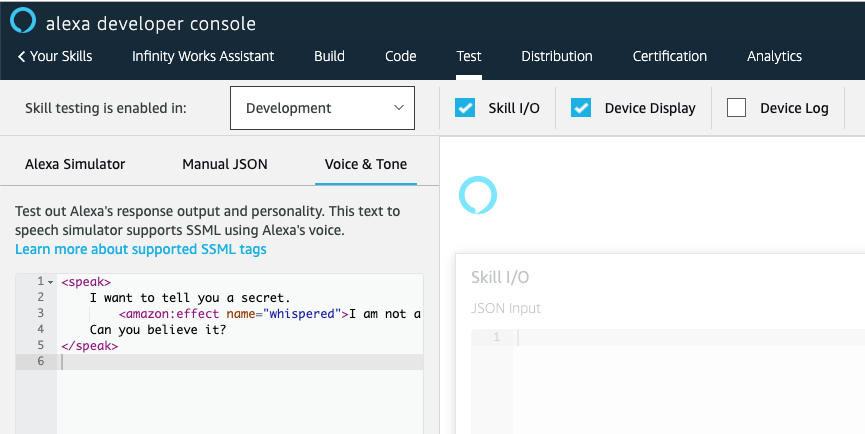

If you want to play about with SSML, the Alexa Developer Console provides a sandbox under the “Test” tab, which allows you to write SSML and have Alexa say it. This way you can identify the best way to output what you want Alexa to say, and experiment with tones, speeds, emphasis on certain words etc to make her feel more human:

Wrapping Up

And that’s it for this post, hopefully that gives you an idea of where to start if you’ve not done Alexa or Javascript development before (like me!) In the next post I’ll be touching on how to unit test Skills using Javascript frameworks.

Whilst writing this post, Amazon have been sending me step-by-step guides on Alexa Development which I think would be useful to share too, so if you get chance take a look at these as well. And you don’t even need to be a coder to get started with these! Until next time…

Design your Voice Experience

Identify your Customers

Write your Script

Define your Voice Interaction

Build your Front End, Your Way

Developer Console

Command-Line Interface

Third Party Tools – no Coding Required!

Build the Back-End

Start with AWS Lambda

More Tools – No Back-End Setup Required